The Rebel of Greek Tragedy

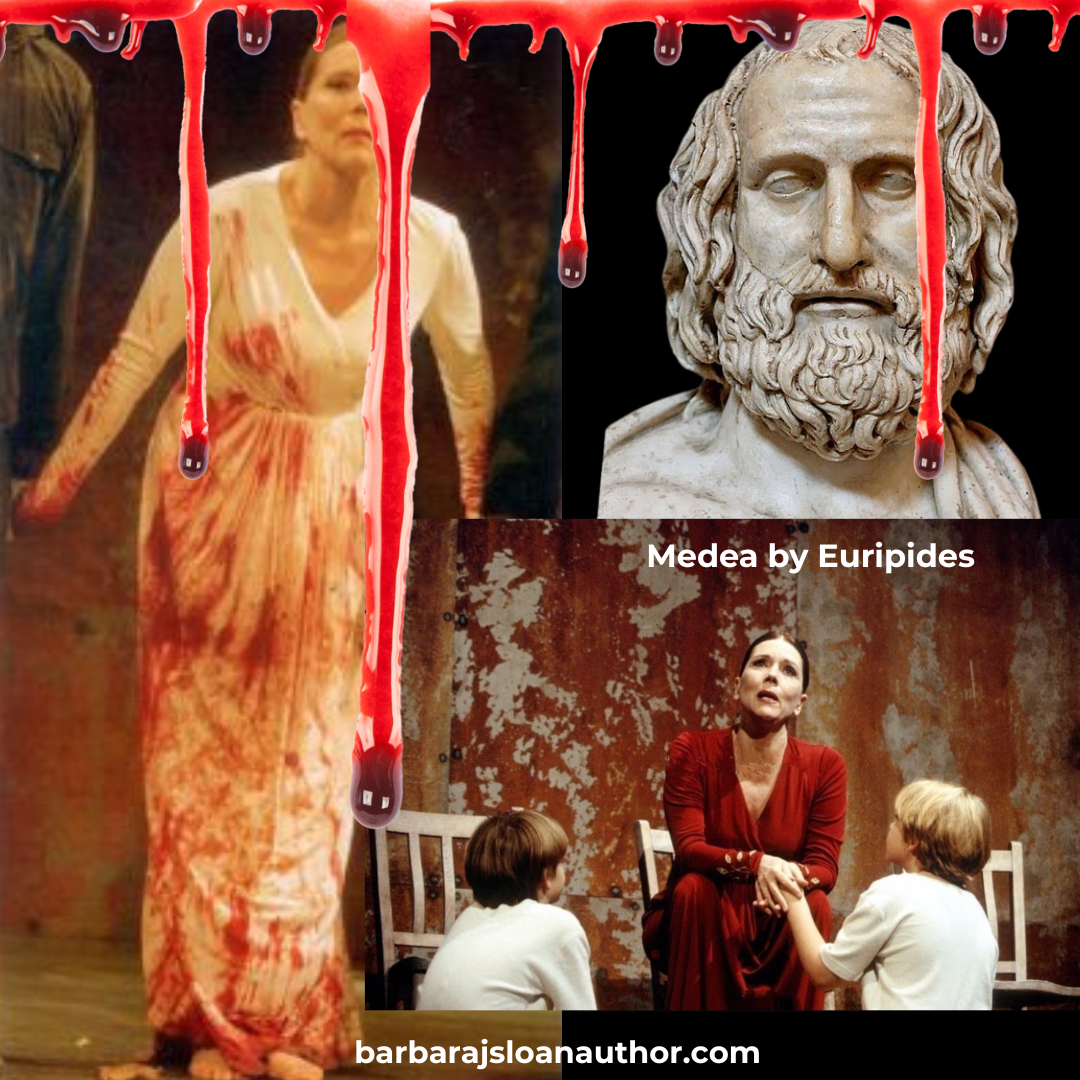

Diana Rigg in Medea by Euripides

Blog 61

“There is just one life for each of us: our own.”

Medea in Euripides’ Medea

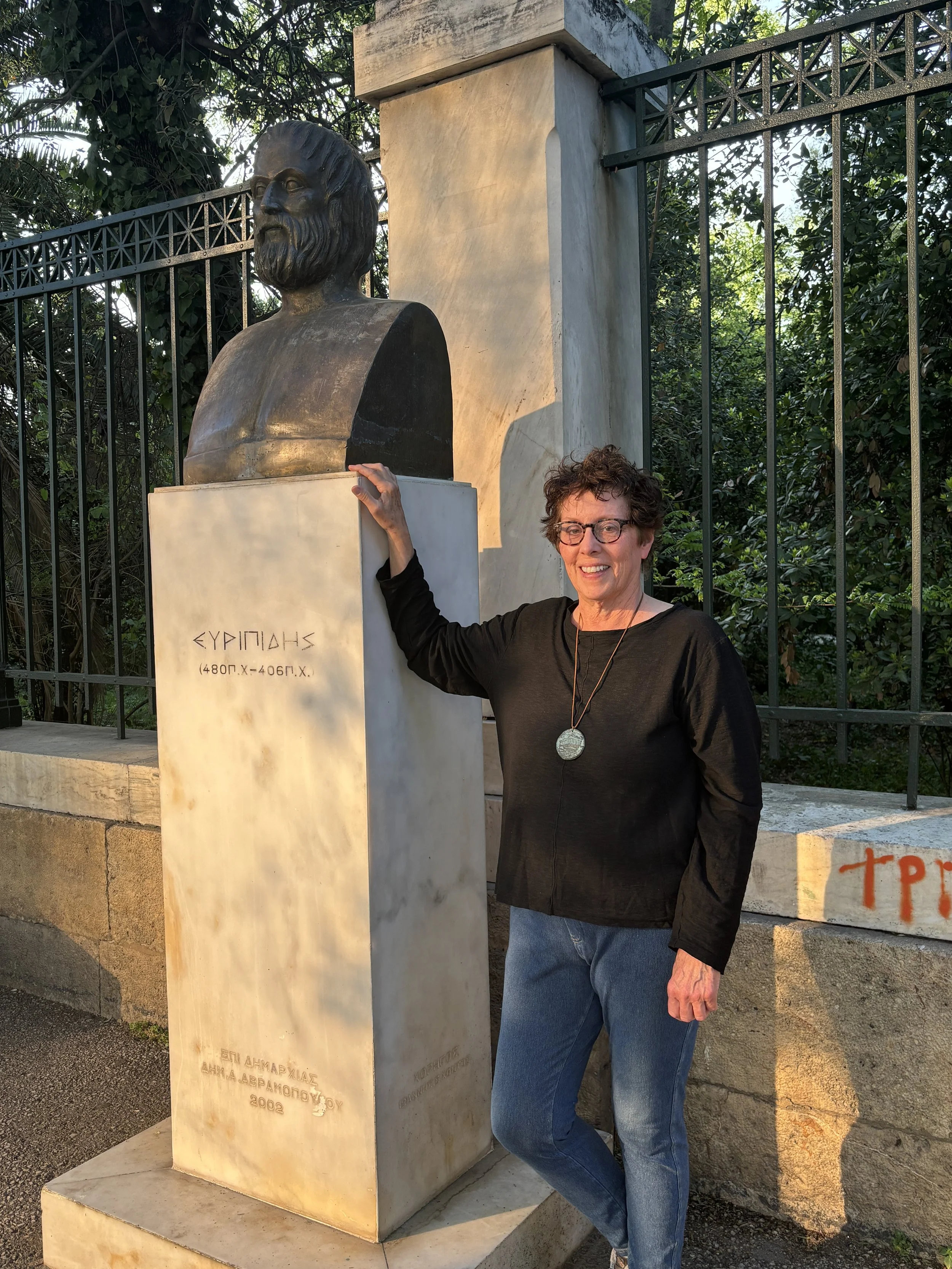

Today is likely the birthday of the Greek dramatist, Euripides. His play Medea (quoted here) is as tragic as it gets, so first let us have a joke from Andreas Nomikos, a wonderful Greek theatre designer and professor I knew in graduate school. In ancient Greece, a man goes to a tailor to get his trousers sewn back up. The tailor asks: “Euripides?” The fellow replies: “Yes. Eumenides?” Okay, it is corny, but Andreas thought the jest was hysterical, so I always laughed every time he told it because he was such a dear man.

In thinking about the ancient Greek drama of Andreas’ birthplace, names like Sophocles, Aeschylus, and Euripides quickly surface. Among them, Euripides stands out as the most modern of the three — not just in style, but in substance. His plays are raw, psychologically complex, and unapologetically critical of society, the gods, and human nature.

Euripides was born around 480 BCE, probably on the day of the famous Battle of Salamis. He lived during the height — and decline — of Athens' golden age, witnessing both its cultural flowering and the brutal reality of war, particularly the Peloponnesian War. These experiences sear his writing, giving his tragedies a darker, smoking, introspective edge. Although he wrote over 90 plays, only 18 or 19 survive in full today. Some of the most famous are: The Trojan Women, Medea, Electra, The Bacchae, and Hippolytus.

Author with statue of Euripides in Athens

Despite his prolific output and his stature today, Euripides was not particularly popular in his own time. His work challenged conventions — both dramatic and social — which often alienated the conservative judges of Athenian drama festivals. Ironically, these bold choices are precisely what make his plays so compelling today.

Euripides breaks molds and disrupts literary conventions. While his predecessors focus on fate, heroism, and divine justice, Euripides turns his attention inward — to the minds of his characters and the messy moral dilemmas they face. Thus, he develops into more than a writer of tragedies — he is a provocateur, and, arguably, theatre’s first great psychologist. His scenes often feel like naturalistic dialogue centuries ahead of their time. The struggles are as mythic as other Greek playwrights, but the emotions feel painfully human.

To me, one of the most appealing aspects of Euripides is that he gives women a voice. Unlike most of his contemporaries, this playwright pays significant attention to female characters, portraying them as intelligent, powerful, and deeply emotional. Medea, perhaps his most controversial heroine, is a foreign woman who is scorned by her husband — and she responds with a shocking act of vengeance by killing their sons.

Euripides forces the audience to grapple with her pain, her sense of betrayal, and the societal structures that have failed her. He crafts a powerfully startling work about regicide and infanticide with his Medea. But Euripides doesn’t paint her simply as a villain. In 1993, a few days before I saw the London production, I accompanied my then 16-year-old daughter Elin to Wyndham’s Theatre to see Diana Rigg in the title role. When I picked her up, her eyes were as round as the full moon above us. “How was it?” I asked. “You’ll just have to see it. I don’t want to spoil it for you,” she gasped.

Euripides creates meaty roles — emotionally explosive, psychologically layered, and theatrically electrifying. So when you see the play Medea, featuring one of the most iconic female roles in theatre history, the actor playing her has to walk a tightrope between empathy and horror.

My own watching of Diana Rigg’s Medea was harrowing. The performance was full of everything you want in a Greek tragedy: banishment, blood, murder, revenge, deceit, the flaunting of male strength, the fierceness of a scorned wife, the rage of love, the violence created from the tension between maternal attachment and the desire to inflict utmost pain. This production became etched in my memory through Peter J. Davison’s intriguing set made of rusty corrugated metal panels that crashed and fell with alarming reverberations as the play drove to its unnerving end.

And with another Euripides work, I really dug deep when designing The Trojan Women. In this play, Euripides strips away the glory often associated with war. He fails to show us victorious generals or noble deaths; instead, we see grief-stricken women, the ruins of civilization, and the human cost of conquest. Written during the Peloponnesian War, this work is a daring critique of Athenian militarism. And as with other plays of his, it bestows presence and power upon women.

Euripides died in 406 BCE — ironically, just a few months before Sophocles. Though he never achieved the fame of his peers in his lifetime, his work gained immense popularity after his death. Roman playwrights admired him. Renaissance scholars rediscovered him. Modern directors still stage his plays across the world.

Why? Because Euripides was willing to dig for the Truth — about power, gender, divinity, justice, and the human psyche. His characters are never marble heroes; they are messy, flawed, and heartbreakingly real. In a world that still grapples with similar issues, Euripides feels less like an ancient dramatist and more like a contemporary voice. For theatre lovers, he is not just a historical figure — he is a kindred spirit: Someone who knew the stage was not just for entertainment, but for asking the hardest questions.

“There is just one life for each of us: our own.” And Euripides certainly lived his own life!